Credit Intermediation and the Transmission of Macro-Financial Uncertainty: International Evidence

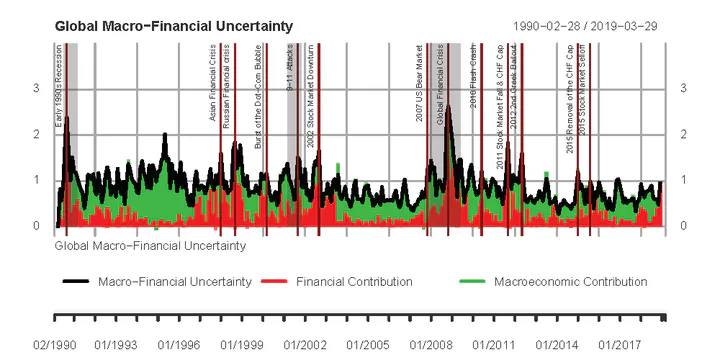

This figure depicts our macro-financial uncertainty measure, additionally reporting contributions of macroeconomic and financial market variables. We also highlight NBER-recessions in gray and indicate and label certain economic events of global influence by a red line.

This figure depicts our macro-financial uncertainty measure, additionally reporting contributions of macroeconomic and financial market variables. We also highlight NBER-recessions in gray and indicate and label certain economic events of global influence by a red line.Conclusion

In this paper, we put forward a new measure of global macro-financial uncertainty and study its effects on GDP growth in a panel of 24 OECD countries. To evaluate the effects of surges in macro-financial uncertainty, we use local projections and allow for nonlinearities in the responses of GDP growth with regard to the state of the respective banking sector at the country level. While we find that uncertainty generally does have an adverse impact on economic growth in a sample of advanced (OECD) economies, the magnitude of the effect strongly depends on the state of the banking sector, suggesting that an uncertainty shock is strongly reinforced when credit intermediation is distressed. Furthermore, we find that the origin of uncertainty is important for its transmission.

Our results therefore suggest a key role of the financial view of the transmission of uncertainty. This suggestion, in turn, implies that a healthy banking sector increases systemic resilience vis-á-vis uncertainty shocks. Our paper contributes to the literature by explicitly distinguishing between macroeconomic and financial market uncertainty on the one hand and the state of financial intermediation on the other.

Our results have broader implications for policy-makers. In particular, the results imply that certainty about future policies is especially important in the context of distressed credit intermediation, as uncertainty shocks are approximately three times more harmful in such a macroeconomic environment compared to cases where the banking sector is well functioning. From a policy perspective, uncertainty typically surges when policy-makers tackle structural issues in the context of economic policy, e.g., issues related to trade, labor markets or competition policies. While such structural reforms are typically initiated in crisis periods when the sovereign is confronted with serious funding issues and higher bond spreads, our results suggest that structural reforms should rather be implemented in relatively calm periods characterized by a healthy banking sector, as such attempts at reform typically lead to a surge in uncertainty. While the translation of these results might be difficult at the national level, as strategic thinking implies a low probability that unpopular structural reforms are implemented in good times by politicians who want to be reelected, the results are relevant for international lenders such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as the implementation of difficult structural reforms may be less costly and thus more rewarding if these reforms are postponed to a period when the banking sector is no longer distressed. While the costs in terms of output loss could be reduced in such a case, the practical problem of the enforcement of these reforms – long after the lending has taken place – admittedly remains a practical hurdle.